Pagos, or terroir in sherry

Some time ago, I was asked why the sense of ‘terroir’ doesn’t exist in sherry wines. My short answer was that it does exist, but that most producers have forgotten about its importance, or at least they’re often not communicating it to consumers. However there’s much more to say, so I decided to write a longer reply.

Terroir can be defined as the combination of micro-climatic elements that have an influence on the grapes and therefore the resulting wine. The composition of the soil, altitude, proximity to the sea, orientation of the vineyard, exposure to winds, local yeast populations… as well as viticultural decisions that are related to this, like planting and pruning methods, moment of harvest, etc.

When we talk about terroir in sherry, there is of course the importance of the Albariza soil and the general location close to the sea which sets it apart from most other wine regions in the world. However when we go into more detail, we have to talk about Pagos. Pago is a Spanish word often translated as vineyard, but that’s incorrect. There are multiple vineyards or viñas in one pago – they can have different owners but with similar characteristics, so it’s better to name it a vineyard district or vineyard cluster. Each pago produces grapes with distinctive features.

Jerez Superior

Every single pago has a unique fingerprint that can shine through in the resulting wine

The term pago is by no means a new invention. Documents dating as far back as the 18th century make reference to pagos and the defining features that differentiate them from one another. These documents also substantiate the fact that some of these pagos are the oldest vineyards in Spain and in Europe.

There was a vineyard boom from a total surface of 10.000 ha in 1968 to around 23.000 ha in 1978, but ten years later the effects of this boom were already undone. Sunflowers and solar panels replaced the grapes in the 1990s and vines were uprooted in exchange for European subsidies. Nowadays there is only around 7000 ha left, spread over +/- 40 pagos, which can range from 2 ha to over 1500.

The finest plots on albariza soil form an area known as Jerez Superior. While officially recognized by the Consejo Regulador, the distinction barely makes sense. Nowadays 90% of all vineyards are in this superior zone, simply because they abandoned all the lesser plots.

Classic pagos: Macharnudo, Carrascal, Añina, Miraflores…

For the Jerez area the most renowned pagos are Macharnudo (an area that was already planted with grapes some 3000 years ago – the best proof of its quality), Carrascal and Añina. For Sanlúcar, the most important name is Miraflores. Around El Puerto de Santa María, these are Balbaina and Los Tercios. These classic pagos were first listed around 1868 in a brochure by Diego Parada y Barreto and a shortly after in a book by Henry Vizetelly. Their association of certain pagos with higher quality caused an important increase of single-vineyard wines and consumers looking for wines from specific pagos.

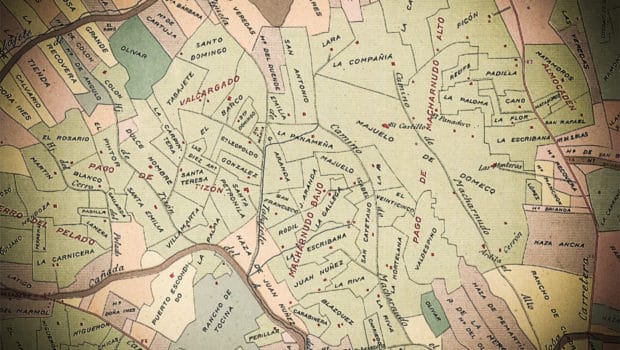

A great resource is the Plano parcelario del término de Jerez, or the parcel map of Jerez. The version drawn in 1904 can be found online in a digital version (I’ve noticed it is sometimes unavailable).

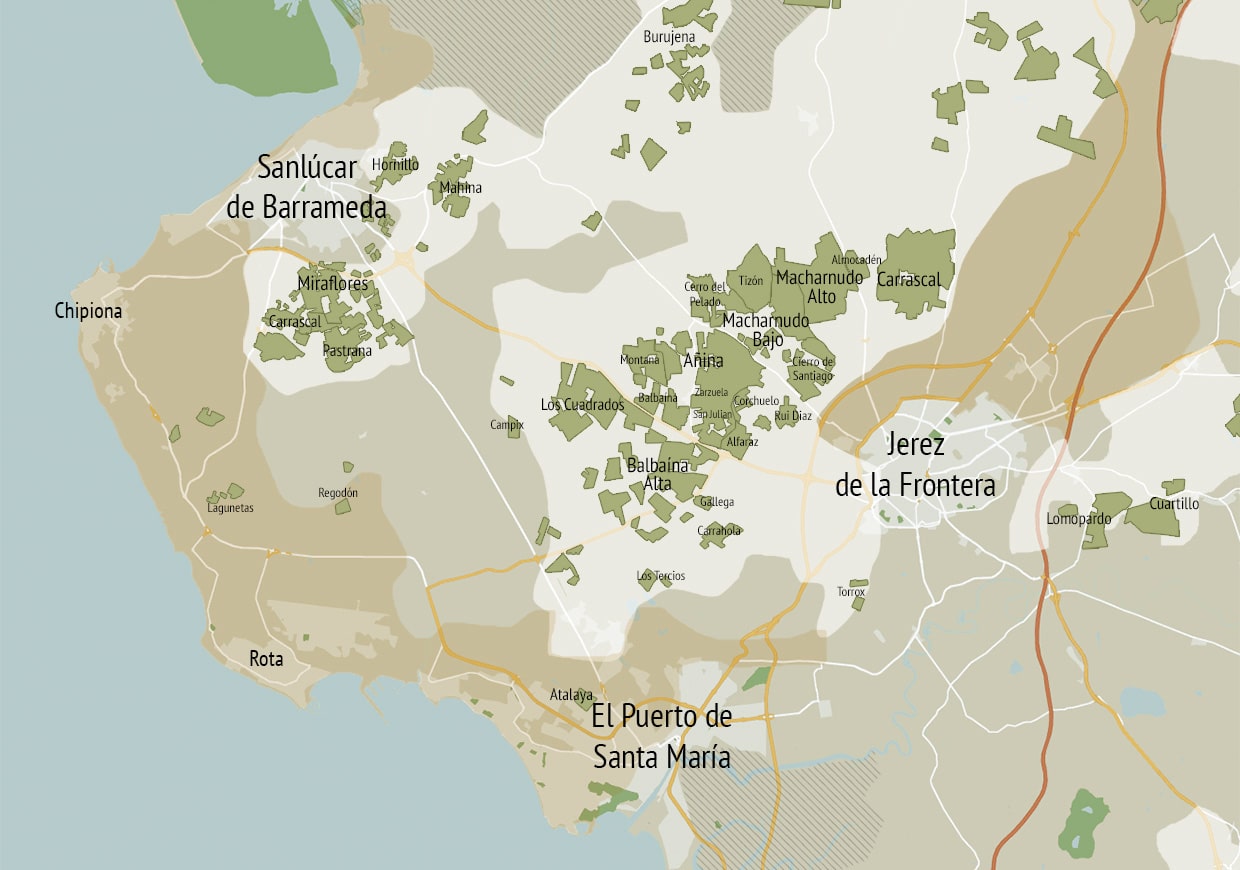

Here’s a more up-to-date version that I made in 2020.

(while the pagos are historically larger, this only includes areas that are actually planted today)

Other pagos in the sherry region

Back in 1868, the sherry region had 134 documented pagos, compared to around 40 today. Here’s a list of the most important: Almocadén, Añina, Atalaya, Balbaína, Burujena, Callejuela, Campix, Carrascal, Cerro Viejo, Corchuelo, Cuartillo, Espartina, Gibalbín, Hornillo, Lagunetas, Lomopardo, Los Cuadrados, Los Tercios, Macharnudo, Maestre, Mahina, Majuelo, Miraflores, Montegilillo, Pastrana, Tizón, Torrebreva and Torrox.

The characteristics of the grapes and the resulting wines varies quite drastically among the pagos (even within them). A few examples. Carrascal is the furthest inland, which means less influence of cool sea air, therefore early ripening and more robust wines, perfect for Oloroso. Macharnudo Alto – possibly the most prestigious of all – has a high elevation and a very pure limestone soil, hence its wines show a specific chalky character. Traditionally excellent for Fino and Amontillado production.

Balbaina and Añina, as well as Los Tercios, are closer to El Puerto de Santa Maria, they have more exposure to poniente winds from the sea and produce the lightest, most elegant wines, usually Fino. To a certain extent it also be explained by small variations within the soil type that we generally call Albariza. Read more about this in my article Albariza revisited: Antehojuela, Tosca Cerrada, Barrajuela

Viña El Majuelo – El Castillo in Macharnudo Alto, at the centre of the old Domecq vineyards

Within these zones, some specific vineyards were considered more noble than others and they soon became brand names on their own. Some examples include Viña Botaina, Viña El Majuelo (the castle that adorns the labels of old Pedro Domecq bottles), Viña AB (a name that lives on in the Amontillado Viña AB) or Pastrana near Sanlúcar.

Fino vs. Manzanilla

Even the difference between a Fino and a Manzanilla, often one of the things that seem difficult to explain, comes down to the different pagos. The terroir around Sanlúcar is slightly cooler than in Jerez, more humid and with slightly less pure Albariza. Historically a Manzanilla wasn’t even considered to be sherry, but over time the idea grew that both are variations of the same wine, just expressed differently because of the specific conditions.

Loss of individuality

High volumes often lead to generalized profiles and the loss of individual qualities.

In the old days, sherry bodegas had their own vineyards, they knew exactly which grapes they were working with and which character they could aim for. Nowadays this individuality is less common. The majority of bodegas sold off their vineyards over the past few decades, which means nowadays they’ve come to rely on larger cooperatives which group vine growers. This also means the grapes come from different pagos and the individual characteristics are lost.

Last but not least the expansion and industrialisation of the 1960’s and 1970’s, as well as the crisis that came after that, caused a fundamental change of focus, towards more volume, more consistency and lower costs, instead of higher individual quality.

The result is that today there are hardly any (wide-scale) single-vineyard wines left – Valdespino Inocente is probably the best known exception. Few producers disclose the provenance of their grapes, partly because soleras go back decades so you can’t change from one day to another. Exceptions exist though: it may seem surprising that the most popular Fino Tio Pepe still mentions its pagos Macharnudo and Carrascal on its labels, proving that quality and quantity can effectively go hand in hand.

The revival of terroir

The idea of terroir is common in all prestigious winemaking regions, but in the D.O. Jerez-Xérès-Sherry there seem to be two contrasting aspirations: one that aims for consistency (always the same quality of wine, year after year, in high quantities) and one that stresses individuality among specific wines.

Now that consistency has become easier to achieve and the long crisis has more or less stabilized, we currently see a small revival of individuality, fuelled by initiatives like Equipo Navazos (who explain the context of each wine as much as they can) and young winemakers who work on a very small scale, with a high transparency and with respect to the classic foundations of this unique wine region.

Ramiro Ibañez is a good example – he’s working in specific plots of land, keeping the grapes separate from others and maturing a lot of his wines in small batches or even single casks to highlight their individuality. His friend Willy Pérez is doing the same on his father’s terrains, producing an unfortified vintage Fino as well as other interesting ideas from the past.

Highly individual sherry wines

We expect this trend to continue in the following years. Lustau released a series of wines from the three key cities. Which bodega will be the first to have a series of wines, identical in all aspects except for the pago that provided the grapes (update: it’s here and it’s called Pitijopos)? We can learn so much from it.

The same trend towards higher individuality will probably lead to more vintage wines, more single cask releases, more ‘snapshot’ bottlings of the same wine at different moments, more experiments with pagos and grapes and eventually to a revaluation of terroir in general by bigger bodegas as well. In the sherry region, so many (un-)modern ideas are still waiting to be put into practice.

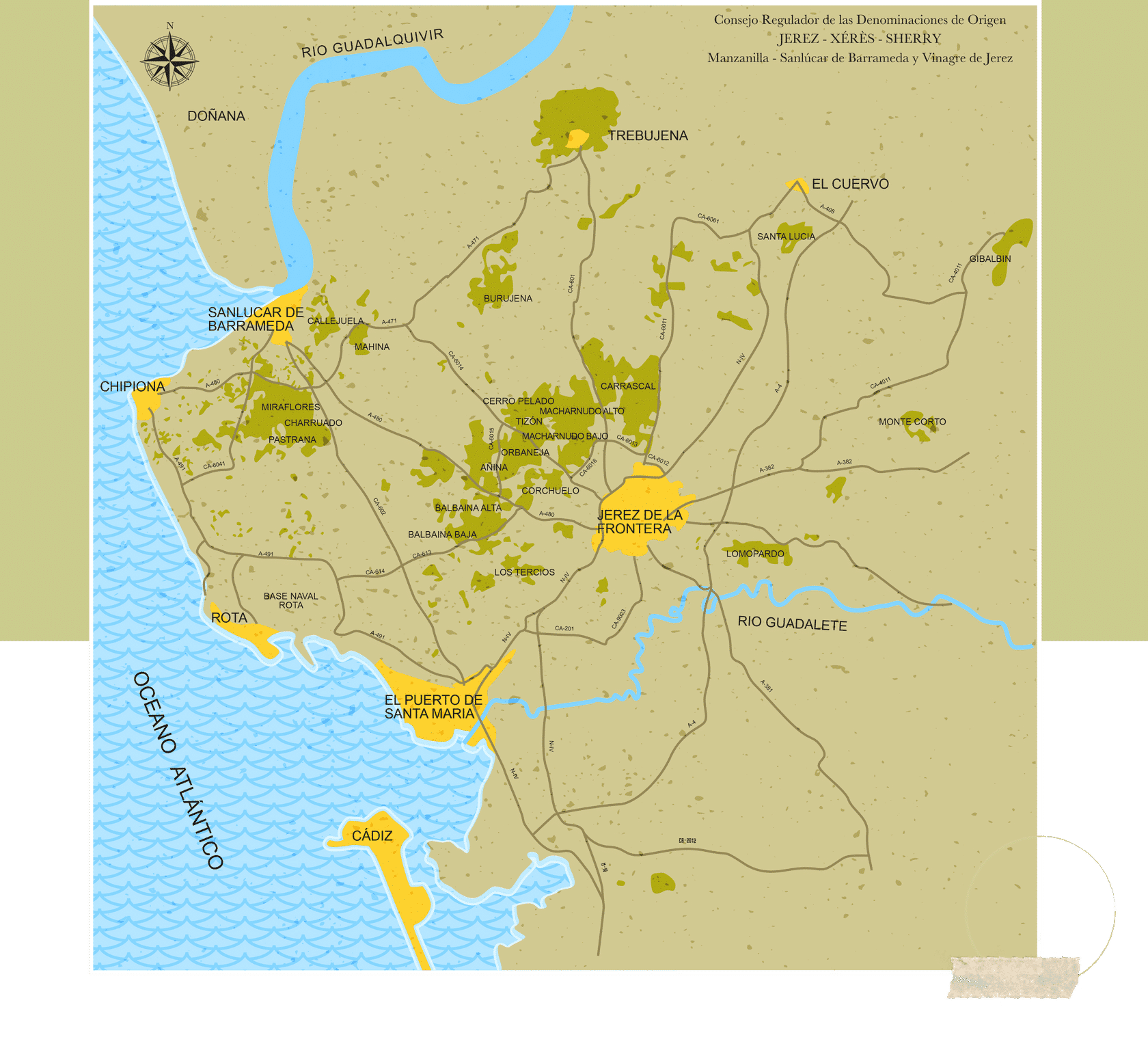

Official map of all the pagos belonging to the D.O.

In recent years the Consejo Regulador has been putting a new spotlight on pagos, under the influence of young winemakers. In 2015 they published an official map of all the pagos belonging to the Designation of Origin. (click to enlarge)

There is also the official list of all the delimited pago areas, down to the smaller geographical units.

Pingback: “The Jerez terroir challenge” by Jefford and others | undertheflor.com

Pingback: The Night Harvest – Sherry Bodegas in Jerez, Sanlucar and El Puerto